Kouwenhoven found guilty

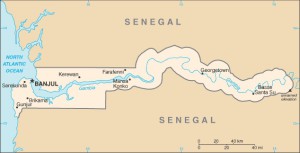

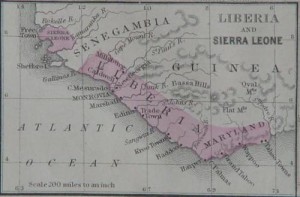

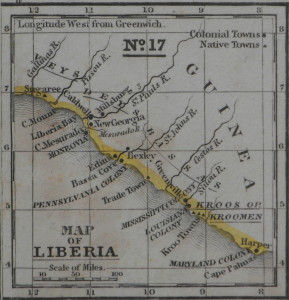

It was an historic day, April 21, 2017. I had travelled to ‘s-Hertogenbosch, colloquially known as Den Bosch, the Netherlands, for the final stage of a trial that had lasted for too long: since 2005, when the Dutch businessman Guus Kouwenhoven was first arrested in the Netherlands. On April 17, 2017, the Appeal Court in Den Bosch was to deliver its final decision in the trial of Guus Kouwenhoven, in Liberia better known as ‘Mr Gus’, accused of violating the UN arms embargo imposed on Liberia during the civil war and illegal arms transactions benefiting former president Charles Taylor. The Dutch businessman was also accused of war crimes in Liberia and the neighbouring republic of Guinea between 2000 and 2002. For the background of the accusations and the details of his trial, see my February 8 posting, after the re-opening of his trial on February 7, 2017.

April 21, 2017. In a crowded court room, filled with reporters and photographers of the national and international press, as well as interested people including myself, the three judges presented their findings and the conclusions of their deliberations. The presiding judge presented already in the first few minutes of the session the Court’s decison: the Appeal Court found Guus Kouwenhoven, 74, guilty of illegal arms trading and accessory to war crimes committed by armed forces of former Liberian president Charles Taylor and Guinea. The timber baron, once member of the prestigious Quote500 society – a listing of the 500 richest people in the Netherlands – was sentenced to 19 years in prison, a year less than the maximum penalty of 20 years. The court ordered his immediate arrest.

April 21, 2017. In a crowded court room, filled with reporters and photographers of the national and international press, as well as interested people including myself, the three judges presented their findings and the conclusions of their deliberations. The presiding judge presented already in the first few minutes of the session the Court’s decison: the Appeal Court found Guus Kouwenhoven, 74, guilty of illegal arms trading and accessory to war crimes committed by armed forces of former Liberian president Charles Taylor and Guinea. The timber baron, once member of the prestigious Quote500 society – a listing of the 500 richest people in the Netherlands – was sentenced to 19 years in prison, a year less than the maximum penalty of 20 years. The court ordered his immediate arrest.

I was immensely relieved! On my way to Den Bosch I had reflected on the possibilities. The accused could be acquitted and hence would be a free man – as had happened in 2008 – or he could be found only partially guilty and sentenced to just a few years in prison – as had happened in 2006, when he was only found guilty of illegal arms trading and sentenced to 8 years in prison. Another option was that he was found guilty, but that the judges, considering his age and allegedly fragile health, would condemn him to pay a heavy fine (although that would of course be no pain for the wealthy businessman). The fourth and last possibility was that he would be found guilty and sentenced to 20 years behind bars, the maximum penalty requested by the Public Prosecutor on February 10, 2017.

I felt an immense joy and satisfaction when I heard the presiding judge saying that the court found Kouwenhoven guilty of both accusations. Personally, I have never had any doubt of his involvement and responsibility. Knowing Liberia, I know that in order to do business in this country you have to be on good terms with the ruler(s) and the fact that ‘Mr Gus’ had decided to voluntarily stay in Liberia, making (much) money, means that he had opted for collaboration with Taylor. Besides, his personal relations and business deals with the warlord-turned-president, his eagerness to engage in business with him and make much money, unequivocally show his complicity and role in Liberia’s civil war that cost over 200,000 lives and wounded and traumatized maybe as many as a million people.

I felt an immense joy and satisfaction when I heard the presiding judge saying that the court found Kouwenhoven guilty of both accusations. Personally, I have never had any doubt of his involvement and responsibility. Knowing Liberia, I know that in order to do business in this country you have to be on good terms with the ruler(s) and the fact that ‘Mr Gus’ had decided to voluntarily stay in Liberia, making (much) money, means that he had opted for collaboration with Taylor. Besides, his personal relations and business deals with the warlord-turned-president, his eagerness to engage in business with him and make much money, unequivocally show his complicity and role in Liberia’s civil war that cost over 200,000 lives and wounded and traumatized maybe as many as a million people.

The Appeal Court’s decision

It is interesting to focus here on three important aspects of the Appeal Court’s ruling.

First, the presiding judge emphasized that Guus Kouwenhoven knew that the arms he illegally imported and distibuted in Liberia were being used in a merciless war and by rebels who committed war crimes and human rights violations resulting in many innocent victims. He was not politically or ideologically motivated, the judge continued, but only financially. He just wanted to increase his profits from his two logging firms, the Oriental Timber Company (OTC) and the Royal Timber Corporation (RTC).

Secondly, and this is very important for future trials of war criminals, the Dutch judges accepted the testimonies of witnesses as important evidence – even though there were some minor inconsistencies in their declarations. The court judged that the time factor and the traumatic experiences of the witnesses formed acceptable reasons for the inconsistences and did not warrant to reject their testimonies. I was surprised to hear the judge say that Kouwenhoven had tried to bribe and intimidate witnesses in Liberia. This certainly isn’t something you would expect from somebody who is innocent.

Finally, the Court of Appeal’s decision sets an important (legal) precedent for corporate responsibility for war crimes. International criminal law specialist Dieneke de Vos has elaborated here on this aspect.

Applause from abroad

Human rights groups, advocacy groups and organizations working to prosecute and try war criminals were unanimous in their positive and enthousiastic reaction to the Appeal Court’s decision. By finding Kouwenhoven guilty, the Dutch judges have greatly supported their cause: the fight against impunity. Guus Kouwenhoven is only the fourth ‘big fish’ condemned for his role and responsibility for atrocities committed in the West African region, and notably in Liberia. His partner-in-crime and in business, Charles Taylor, has been sentenced to 50 years in prison by the Special Court for Sierra Leone in 2013. Please note that Taylor was prosecuted and condemned for his role in the civil war in Sierra Leone – NOT for his responsibility for the human rights violations and war crimes committed by his troops in Liberia. Charles Taylor’s son Chuck was tried in the US where judges sentenced him to 97 years in prison for his role in torturing political opponents of his father in Liberia. His trial had been made possibe because of his dual citizenship. The notorious arms dealer Viktor Bout aka ‘the Merchant of Death’ – who also supplied arms to Charles Taylor in Liberia – was sentenced to 25 years in prison in 2012, also in the US. The Tajik (from Tajikistan, a former USSR-republic) Viktor Bout stood trial on terrorism charges – NOT for his responsibility for the war crimes committed by his ‘friend’ Charles Tyalor and his National Patriotic Front of Liberia, NPFL.

Be that as it may, these condemnations contrast sharply with the reality in Liberia where war criminals and human rights violators walk free. Former warlord Prince Johnson whose men tortured then President Samuel Doe to death is now a senator and even a presidential candidate for the October elections. Other warlords like Alhaji Kromah, ULIMO-K leader, and George Boley, LPC leader, and the notorious General Butt Naked – who confessed before Liberia’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) to have killed 20,000 people and to have committed ritual murders and acts of cannibalism – have never been accused or prosecuted. In Liberia impunity reigns. There is no rule of law. Prosecution of war criminals takes place in other countries: in the US, in the Netherlands, in Belgium, in Switzerland.

Martina Johnson was a feared female rebel leader, fighting with Charles Taylor’s NPFL. She was feared for the atrocities against Krahns and Mandingoes, including torture and murder, that had taken place under her command. After Taylor’s forced resignation, in 2003, she fled to Belgium, where she was arested in Ghent at the end of September 2014. After her arrest she was accused of war crimes and crimes against humanity. Two months after Martina Johnson’s arrest ULIMO-K fighter Alieu Kosiah was arrested in Switzerland. Alieu Kosiah is accused of involvement in and responsibilityof human rights abuses and war crimes committed in Voinjama, Foya, Kolahun and Zorzor from 1993 to 1995.

In May 2014, Tom Woewiyu – Charles Taylor’s former right hand man, co-founder of the NPFL, warlord and, during Taylor’s presidency, president pro tempore of the Liberian Senate – was apprehended at Newark International Airport, USA. He was charged on no less than 16 accounts. He was specifically accused of lying about his participation in the NPFL and the CRC (Central Revolutionary Council, a breakaway faction of the NPFL), and about whether he had ever been involved in an atempt to overthrow the government of a country. His arrest though might have been inspired by opportunistic reasons. The US role in Liberia has always been one of geo-political interests and economic benefits. This is not the right place to dwell here on the historical role of the US in Liberia. Interested readers are referred to my 2015 publication, ‘Liberia: From the Love of Liberty to Paradise Lost’ (see below).

In May 2014, Tom Woewiyu – Charles Taylor’s former right hand man, co-founder of the NPFL, warlord and, during Taylor’s presidency, president pro tempore of the Liberian Senate – was apprehended at Newark International Airport, USA. He was charged on no less than 16 accounts. He was specifically accused of lying about his participation in the NPFL and the CRC (Central Revolutionary Council, a breakaway faction of the NPFL), and about whether he had ever been involved in an atempt to overthrow the government of a country. His arrest though might have been inspired by opportunistic reasons. The US role in Liberia has always been one of geo-political interests and economic benefits. This is not the right place to dwell here on the historical role of the US in Liberia. Interested readers are referred to my 2015 publication, ‘Liberia: From the Love of Liberty to Paradise Lost’ (see below).

The foregoing inevitably leads to the pressing question: Why has President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Africa’s first democratically elected female president and co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011, never encouraged or initiated the legal prosecution of war criminals in her country? The answer may be too complicated to present here. Critics point at her role in the creation of the NPFL: she was one of its co-founders, together with Charles Taylor, Tom Woewiyu and others. EJS has admitted her role before the TRC, but declared that she withdrew from the NPFL and cut ties with Taylor in an early stage of the civil war when realizing that her former comrade-in-arms Charles Taylor was a ‘ruthless criminal’. I have little doubt that once she will have left – in January 2018 when her successor will be installed – we will hear more details about her past and relations with Charles Taylor.

The foregoing inevitably leads to the pressing question: Why has President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Africa’s first democratically elected female president and co-winner of the Nobel Peace Prize in 2011, never encouraged or initiated the legal prosecution of war criminals in her country? The answer may be too complicated to present here. Critics point at her role in the creation of the NPFL: she was one of its co-founders, together with Charles Taylor, Tom Woewiyu and others. EJS has admitted her role before the TRC, but declared that she withdrew from the NPFL and cut ties with Taylor in an early stage of the civil war when realizing that her former comrade-in-arms Charles Taylor was a ‘ruthless criminal’. I have little doubt that once she will have left – in January 2018 when her successor will be installed – we will hear more details about her past and relations with Charles Taylor.

Back to Guus Kouwenhoven. During the trial his lawyer, the famous Dutch criminal lawyer Inez Weski told the judges – to explain her client’s absence – that Kouwenhoven was in South Africa ‘for medical reasons’. Immediate after the Court’s decision on April 21 she anounced that she was (again) going to the Supreme Court to fight the Court’s decision and also to the European Court of Human Rights to prevent her client’s arrest. Chances to be successful are slim, in my opinion. Anyway, these moves do not suspend the arrest warrant.

There does not exist an extradition treaty between the Netherlands and South Africa for the crimes committed by Kouwenhoven. However, South Africa has joined the European Convention on Extradition (1957) which makes his extradition possible. This consideration supposes that he is in South Africa, which is far from sure. His lawyer refuses to reveal her client’s whereabouts. He might be in South Africa, but could also be in another African country. E.g. in Congo-Brazzaville, where he had (still has?) business interests and certainly business associates who are willing to help him hide for the Dutch justice. The latter should be congratulated. The War Crimes Department, the public prosecutor and the entire Dutch judiciary have done a tremendous job, a shining example for a country like Liberia where – it hurts to say – no justice exists.

The foregoing is partly based on the author’s book ‘Liberia: From The Love of Liberty to Paradise Lost’, published by the African Studies Centre Leiden (Leiden, 2015). The book is available online (free access): https://openaccess.leidenuniv.nl/handle/1887/33835

The original post dated May 7 has been slightly modified on May 15. It concerns here the reference to the European Convention on Extradition (1957) which was joined by several non-European countries, notably South Africa.