Emigration of former slaves and colored people to the west coast of Africa wasn’t always voluntary, as we have seen in preceding posts. This, however, doesn’t mean that African Americans who left the United States to settle on the other side of the Atlantic were unhappy or embittered. Far from that, in most cases. Few colonists returned to the United States. Most emigrants stayed in one of the American colonies where they had started a new life with better perspectives than what they had ‘back home’, in the United States where they were discriminated and/or held in bondage.

From letters which the settlers sent to their relatives who had stayed behind in the United States, or sometimes to their former ‘owners’, we learn that the new environment included many challenges. Two noteworthy books with letters from emigrants which I can recommend in this respect are Bell I. Wiley’s ‘Slaves No More. Letters from Liberia 1833-1869‘ (University Press of Kentucky, 1980) and ‘ “Dear Master”, Letters of a slave family‘ (Cornell University Press, Ithaca/London, 1978).

American 19th century newspapers contain many articles lauding the American Colonization Society which organized and financed the emigration of former slaves to one of the American colonies, with military, financial and diplomatic support of the US government. Some of these articles are in fact hardly disguised propaganda for a – also – much criticized effort to get rid of a group of undesired people.

However, I also find in some American newspapers letters from colonists who describe their improved status, and express their feelings of gratitude, as well as their happiness with their present situation. One of such letters I have reproduced here.

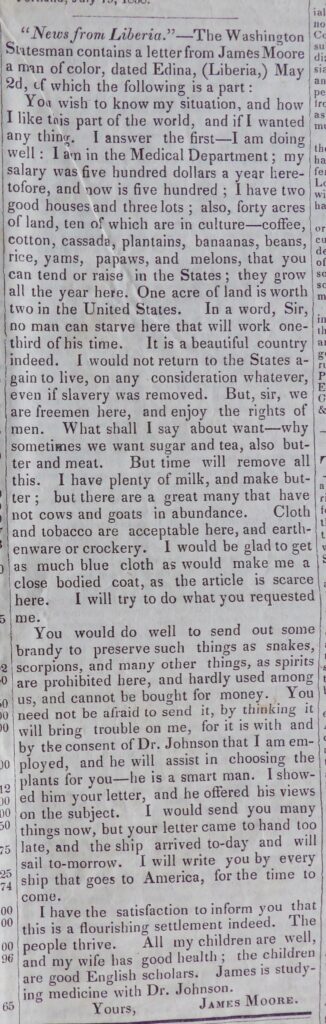

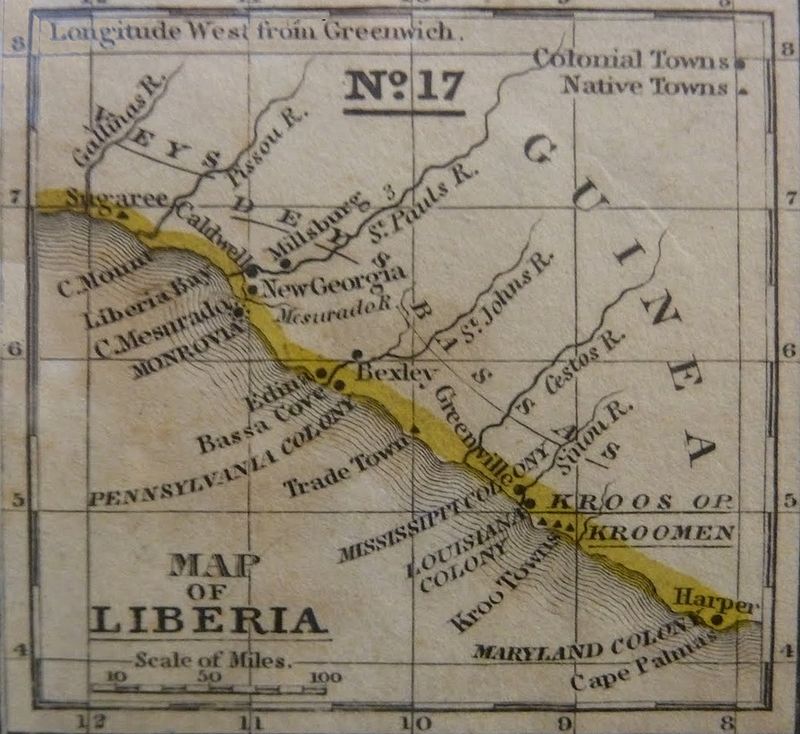

The letter was written by an African American colonist, James Moore, who had settled in Edina, in one of the American colonies created. From it we learn that he was an emigrant with considerable education; he may have been a former slave. The newspaper which contains his letter is ‘The Christian Mirror’ (published in Portland, Maine, one of the so-called ‘free states’ where slavery was not permitted), dated July 26, 1838, and cites from another newspaper, ‘The Washington Statesman’, hence south of the Mason-Dixon line.

The Christian Mirror presents James Moore’s letter, dated May 2, 1838, under the heading “News from Liberia”. It is not known to whom his letter was addressed. Presumably someone he knows well and holds in high esteem (maybe a former employer or slave-owner?).

It reads as follows (the text is reproduced as it appears in the newspaper):

“You may wish to know my situation, and how I like this part of the world, and if I wanted anything.

I answer the first – I am doing well: I am in the Medical Department ; my salary was five hundred dollars a year heretofore, and now is five hundred; I have two good houses and three lots; also, forty acres of land, ten of which are in culture – coffee, cotton, cassada, plantains, banaanas, beans, rice, yams, papaws, and melons, that you can tend or raise in the States; they grow all the year here. One acre of land is worth two in the United States. In a word, Sir, no man can starve here, that will work one-third of his time. It is a beautiful country indeed. I would not return to the States again to live , on any condition whatsoever, even if slavery was removed. But, sir, we are freemen here, and enjoy the rights of men.

What shall I say about want – why sometimes we want sugar and tea, also butter and meat. But time will remove all this. I have plenty of milk, and make butter; but there are a great many that have not cows and goats in abundance. Cloth and tobacco are acceptable here, and earthenware or crockery. I would be glad to get as much blue cloth as would make me a close bodies coat, as the article is scarce here. I will try to do what you requested me.

You would do well to send out some brandy to preserve such things as snakes, scorpions and many other things, as spirits are prohibited here, and hardly used among us, and cannot be bought for money. You need not be afraid to send it, by thinking it would bring trouble on me, for it is with and by the consent of Dr. Johnson that I am employed, and he will assist in choosing the plants for you – he is a smart man. I showed him your letter, and he offered his views on the subject. I would send you many things now, but your letter came to hand too late, and the ship arrived to-day and will sail to-morrow. I will write you by every ship that goes to America, for the time to come.

I have the satisfaction to inform you that this is a flourishing settlement indeed. The people thrive. All my children are well, and my wife has good health; the children are good English scholars. James is studying medicine with Dr. Johnson.

Yours, James Moore