On May 31, I raised the question ‘Liberia’s national symbols – what happened to the national debate?’. Now, a month later, I must confess that I am inclined to answer this question with the tentative conclusion: ‘Liberians are not interested’.

If true, the immediate next question would be ‘Why are Liberians not interested in a debate on the intentions and meanings of the national symbols?’ Is it because a debate on the country’s national symbols is considered to be not relevant? Or is it because people expect that a decision to change symbols like national seal, motto, flag, geographical names would be too costly whereas the country faces other priorities? Or is it because of the fear that any discussion might trigger tension in a country whose population is far from united and still has not overcome the scars of two civil wars?

If true, the immediate next question would be ‘Why are Liberians not interested in a debate on the intentions and meanings of the national symbols?’ Is it because a debate on the country’s national symbols is considered to be not relevant? Or is it because people expect that a decision to change symbols like national seal, motto, flag, geographical names would be too costly whereas the country faces other priorities? Or is it because of the fear that any discussion might trigger tension in a country whose population is far from united and still has not overcome the scars of two civil wars?

History, on the other hand, shows a different picture. It was during the Administration of President William Tolbert (1971-1980) that for the first time in the country’s history decisions were taken to make changes in the area of national symbols. Many generations of Liberians had learned in school about Matilda Newport, and December 1 – ‘Matilda Newport Day’ – was almost sacred. The political activists of the tumultuous 1970s not only wanted political changes and an end to the one-party regime, they also wanted a debate on national symbols. In December 1974, the well-known Dr. Togba-Nah Tipoteh wondered ‘why we say we are interested in unity when we continue to celebrate Matilda Newport Day, a national holiday which glorifies the defeat of one group of citizens by another group of our citizens.’  And even though still in 1975, in celebration of International Women’s Year, the government issued a stamp honoring Matilda Newport, President Tolbert decided to abolish the celebration of December 1 as ‘Matilda Newport Day’. (Source: Svend Holsoe, ‘Matilda Newport: The Power of a Liberian-Invented Tradition’, in: Liberian Studies Journal, Vol. XXXII, Number 2, 2007, pp. 28-42).

And even though still in 1975, in celebration of International Women’s Year, the government issued a stamp honoring Matilda Newport, President Tolbert decided to abolish the celebration of December 1 as ‘Matilda Newport Day’. (Source: Svend Holsoe, ‘Matilda Newport: The Power of a Liberian-Invented Tradition’, in: Liberian Studies Journal, Vol. XXXII, Number 2, 2007, pp. 28-42).

Several Independence Day orators have seized the occasion of ‘July 26’ to express their feelings about the usefulness and appropriateness of the country’s national symbols. Many of these symbols go back to the early days of the Colony of Liberia (1821-1847) and the creation of the independent republic of Liberia by the ‘pioneers’ – as they liked calling themselves – or ‘Americans’ according to the local people.

One of the Independence Day orators questioning the validity of the existing national symbols was Dr. Abeodu Bowen Jones, some 40 years ago, during the Administration of President Tolbert. Dr. Jones pointed out the divisive ideas that characterize the national symbols, even the anthem. A commision was created to review and remove the objectionable parts, and the commission even submitted a report. However, nothing was done do implement its recommendations. In 2008, another Independence Day orator, Dr. Sakui W. G. Malakpa, renewed the debate with his oration entitled ‘Coping with the inevitability of change: our challenges, chances and choices.’ Although I do not intend to present here an exhaustive overview of Independence Day orators and politicians who have raised the subject of National Symbols in public, I do want to mention here Dr. Elwood Dunn’s oration of July 26, 2012, ‘Renewing our National Promise’. In my previous posts dated August 31, 2012 and May 31, 2015. I have already elaborated on Dr. Dunn’s thoughts and statements, so interested readers are kindly referred to these pages. However, I make an exception for the following statement, I quote:

‘Balancing the imbalance’

Dr. Dunn: ‘I told the government that I have been writing and making speeches against  our national decorations and symbols on the basis that they do not reflect our oneness as Liberians.’ He further said: ‘My rejection comes from the perspective that, over our existence as a nation, there have been imbalances. There have been social imbalance, cultural imbalance, economic imbalance and many more. I want us to promote the balance of the imbalance, so that whatever region of the country you come from you can see yourself reflected in our symbols and decorations.’ (italics added by the author, FVDK)

our national decorations and symbols on the basis that they do not reflect our oneness as Liberians.’ He further said: ‘My rejection comes from the perspective that, over our existence as a nation, there have been imbalances. There have been social imbalance, cultural imbalance, economic imbalance and many more. I want us to promote the balance of the imbalance, so that whatever region of the country you come from you can see yourself reflected in our symbols and decorations.’ (italics added by the author, FVDK)

Also in 2014 a symposium was held that received much attention, ‘Reviewing Liberia’s National Symbols to Renew National Identity’ (Paynesville, Liberia).

We may thus conclude that whereas nowadays in 2015 the debate on the national symbols may seem dead, we can expect it to be revived in the near or distant future. Earlier and current internet discussions also indicate that the topic still raises many reactions, both favorable and disapproving.

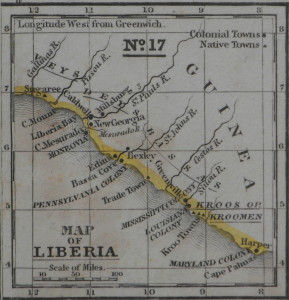

In the meantime the nation’s seal, motto and flag remain unchanged. Also, public holidays such as Pioneer’s Day (January 7), J.J. Roberts Day (March 15), Decoration Day (the third Wednesday of March) and Flag Day (August 14) will continue to be celebrated. Names of streets, towns, and counties will stay as they are: named after white colonial agents (Ashmun, Randall, Mechlin streets in Monrovia – the capital named after US President Monroe) and after the first, white Governor of the Commonwealth of Liberia (Thomas Buchanan) or referring to the place of origin in the US of the first colonists: New Georgia, Virginia, both colonial towns in the vicinity of Monrovia, nowadays part of greater Monrovia, and Maryland County. The latter reflects the former colony ‘Maryland in Africa’ and the small African state of the same name (1854-1857) before it joined the Republic of Liberia, created ten years earlier through the merger of the ‘Colony of Liberia’, ‘Bassa Cove’ and ‘Mississippi in Africa’. See the 1839 map below showing colonial names.

In the meantime the nation’s seal, motto and flag remain unchanged. Also, public holidays such as Pioneer’s Day (January 7), J.J. Roberts Day (March 15), Decoration Day (the third Wednesday of March) and Flag Day (August 14) will continue to be celebrated. Names of streets, towns, and counties will stay as they are: named after white colonial agents (Ashmun, Randall, Mechlin streets in Monrovia – the capital named after US President Monroe) and after the first, white Governor of the Commonwealth of Liberia (Thomas Buchanan) or referring to the place of origin in the US of the first colonists: New Georgia, Virginia, both colonial towns in the vicinity of Monrovia, nowadays part of greater Monrovia, and Maryland County. The latter reflects the former colony ‘Maryland in Africa’ and the small African state of the same name (1854-1857) before it joined the Republic of Liberia, created ten years earlier through the merger of the ‘Colony of Liberia’, ‘Bassa Cove’ and ‘Mississippi in Africa’. See the 1839 map below showing colonial names.